01.16.23

-Marlow Sholander

Within your lifetime will, perhaps,

As souvenirs from distant suns

Be carried back to earth some maps

Of planets and you'll find that one's

So hard to color that you've got

To use five crayons. Maybe, not.

Cell Phone Doorstop

I sit in front of the computer on the first day of my college class. All twelve of my in-person students cannot come down owing to sheer havoc at my facility (an intense assault; a boy throwing three bodily secretions in one cup). There are three boys on my screen who I will never meet in person, residents at a facility over an hour away.

I receive no additional pay for teaching college classes, let alone teaching them for three facilities. One of the facilities told me to give them all the work, and they would get it back to me, but I would never see them on the screen. So be it. It is not as though I will work less hard for them, only differently.

The college classes are considerably more work than my high school ones, but I get to add "college adjunct" to a resume that has not otherwise changed in a decade, one whose further use is unclear. I work for the state, which is inclined to shift me around when they close my facility but not make me start fresh. To whom would I be applying?

On any other first day of classes, I would establish a relationship with the students -- a few of whom I have encountered, but most are faintly familiar faces from passing in the hall -- and feel vaguely professorial in minutes. The litany of chaos over the three-day weekend, which led to a few favored students ending up in serious trouble, rattles me. This is nothing unusual here, where students have always existed in a state of myopia regarding their actions. Still, my resilience is absent.

My breakdown over the weekend feels less like a cathartic revelation from deep in my subconscious and more like a symptom as I sputter while reviewing the syllabus with faces so small on my screen that I could not pick the boys out of a crowd.

I was astounded that they told me moments before the class began that there would be so many students -- the largest number I'd ever worked with in the juvenile justice system -- from five different units. Ordinarily, the units are kept so separate that residents can spend years here and never meet or even know the other exists. They are given to such entrenched tribalism that actual violent gangs form based on the assigned units, and we must try to quash them. When the facility moves a resident onto another unit -- usually because of bad behavior, but occasionally good -- it is like dropping a black ant among fire ants. In short, my college classroom will be a testing ground for the students to act as proxies for their units or reenact neighborhood beefs.

It again emphasizes my degree of underutilization. Given a proper class who can manage to get up for school, I could sand off the rough edges of their illiterate years, shaping incoherence into readability and giving those inclined a map on the road to becoming competent writers.

Daily, I am told I may be able to go on the units to teach if the students behave themselves and enough staff comes in, but not to hold my breath. My parents feel I ought to be guiding the children of global elites rather than another Quackenbush making a career behind razor wire. I don't disagree, but that is not the paradigm I find myself in.

I want to be well-utilized. I am a cellphone used as a doorstop. It works, but that's not what it is for; such misuse will damage it.

Perhaps it is not a great surprise that a detention facility for juvenile felons would not be a functional place. My former one, a tenth the size with crimes a third as severe, worked incessantly (to an obnoxious degree at times) to be functional, receiving the coveted Sanctuary Certification for trauma-informed care months after learning we would close by gubernatorial diktat.

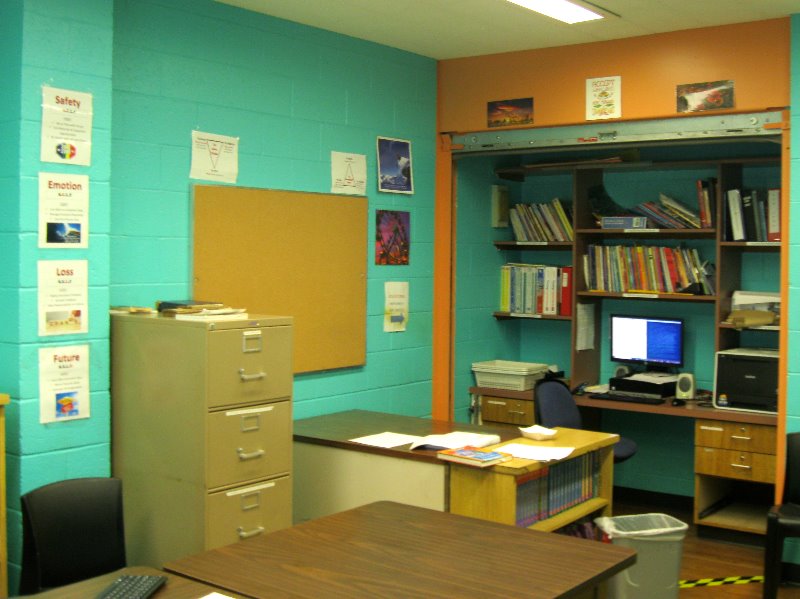

It was easier there, where I had my classroom and consistent tech. I could teach lessons that build on the last and exploit multimedia to communicate my point. I could interact daily with my classes to understand their progress and deficits needing remediation. My worst day of teaching at my old facility resembles my best day here. And my best day at my former facility would be a critical failure when I taught at my summer program for gifted kids or my boarding school for learning-disabled ones. I am a far better, savvier, broader, and more practiced teacher. I have spoken to standing-room convention halls. I have behavior management skills that can get a serial murdering gang member to sit and do a passable job on a worksheet for a middle schooler. I am essentially only asked to do the last. (The student is not hypothetical; I have taught that boy more than once.)

I am the author of eight published books, two unpublished, and dozens of articles for which I have received around $7000; I can write. I can use my long experience to give these kids a massive leg-up. One or two have glimmers of interest, but it is rare. Even then, few have the passion to make them want to practice writing, to say nothing of practicing it instead of sleeping in or playing NBA 2K.

I have much to offer but nothing they want.

last watched: God's Favorite Idiot

reading: The Empty Ones