05.28.19

-Rainer Maria Rilke

If your daily life seems poor, don't blame it, blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to call forth its riches.

Not Mean. But Be.

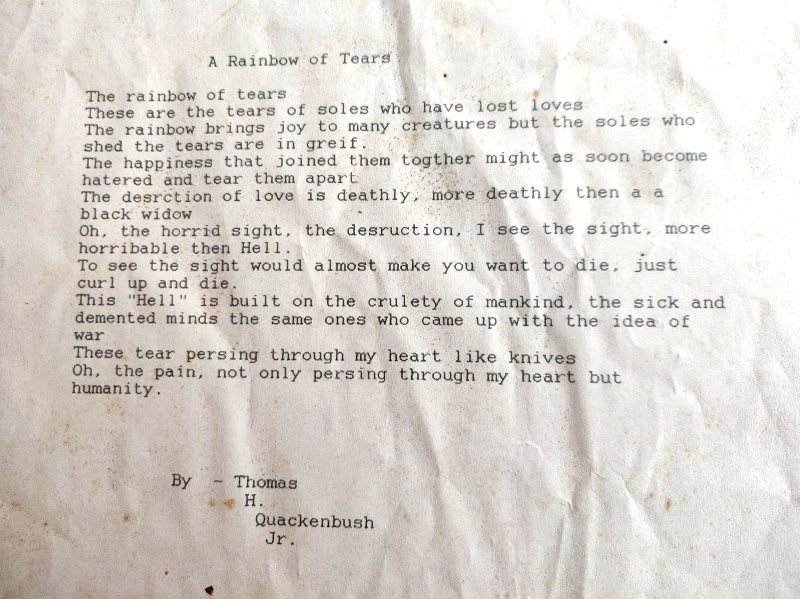

In early middle school, I joined a monthly adult poetry group that met in the back room of the public library. I was a born writer and it manifested in poetry because I assumed the ability to write one thing must be transferable. I remember an overwrought Valentine's poem too morbid for the bulletin board, "A Rainbow of Tears," where I stuffed melodramatic terms in sequence. I waited without reprieve to be called on doing so. That may have been aptitude enough that adults made the mistake of encouraging me.

I was an avid writer of stories then, often using similar (though immature) themes as are found in my books now. I did not join a group for stories. I did not know if such a thing existed. Any writing group in a storm.

(Decades later, I did join a group for short stories. I didn't care for the ego-stroking, condescension, and explosive reactions to mild criticism. It turns out I do not consider writing to be a team sport.)

I was not the poet laureate of Rombout Middle School, though I kept writing poems. They were easy, and adults clucked over them as though they meant something. If a few lines of related images impressed the teachers, they must be in on the grift. People only pretended poetry was meaningful to seem cultured. How else could someone look at a fifth-grade effort titled "As the Crow Flies" and coo at its brilliance?

A black man whose poetry was xeroxed, typewritten words in patterns led the group. He may have been elderly, but everyone was much taller than me at that point and age was difficult to ascribe. He gifted me a copy of his spiral bound, self-published book, priced $20. Its one use to me was as a Magic Eye poster. The meaning of the words was irrelevant to him. He only wanted to draw turbid oceans on a typewriter, and thus reinforced my main prejudice against poetry.

My presence delighted him, though I was younger than any of them by a decade, if not three or four. I was the future of poetry, he gushed. That I took notes on an early nineties PDA astounded him. He made me so nervous I tried never to speak in his presence. New people spiked my anxiety and adults without buffer of my parents. Feeling like a prepubescent fraud about to be exposed did not help that.

I don't remember many of the other in the group. There was a Byronic goth with stringy black hair, who smirked as though he knew we were all fakers. I

In early middle school, I joined a monthly adult poetry group that met in the back room of the public library. I was a born writer and it manifested in poetry because I assumed the ability to write one thing must be transferable. I remember an overwrought Valentine's poem too morbid for the bulletin board, "A Rainbow of Tears," where I stuffed melodramatic terms in sequence. I waited without reprieve to be called on doing so. That may have been aptitude enough that adults made the mistake of encouraging me.

I was an avid writer of stories then, often using similar (though immature) themes as are found in my books now. I did not join a group for stories. I did not know if such a thing existed. Any writing group in a storm.

(Decades later, I did join a group for short stories. I didn't care for the ego-stroking, condescension, and explosive reactions to mild criticism. It turns out I do not consider writing to be a team sport.)

I was not the poet laureate of Rombout Middle School, though I kept writing poems. They were easy, and adults clucked over them as though they meant something. If a few lines of related images impressed the teachers, they must be in on the grift. People only pretended poetry was meaningful to seem cultured. How else could someone look at a fifth-grade effort titled "As the Crow Flies" and coo at its brilliance?

A black man whose poetry was xeroxed, typewritten words in patterns led the group. He may have been elderly, but everyone was much taller than me at that point and age was difficult to ascribe. He gifted me a copy of his spiral bound, self-published book, priced $20. Its one use to me was as a Magic Eye poster. The meaning of the words was irrelevant to him. He only wanted to draw turbid oceans on a typewriter, and thus reinforced my main prejudice against poetry.

My presence delighted him, though I was younger than any of them by a decade, if not three or four. I was the future of poetry, he gushed. That I took notes on an early nineties PDA astounded him. He made me so nervous I tried never to speak in his presence. New people spiked my anxiety and adults without buffer of my parents. Feeling like a prepubescent fraud about to be exposed did not help that.

I don't remember many of the other in the group. There was a Byronic goth with stringy black hair, who smirked as though he knew we were all fakers. I'm sure there were a few middle-aged women writing poetry about love, sex, and cats, but only because there always is in these groups. When I try to envision others, they are all extras from central casting meant to suggest more people were in the room without giving them lines.

I don't know how long I lasted there. It was several months, but not a year. I felt over my head and inferior. I had no business around practiced adults, even if I suspected the practice was literary self-delusion. If I took something from the group beyond their faintly patronizing encouragement -- they treated every word out of me as though I were TS Eliot's Christ Child -- I can't recall it. Poetry seemed false and pretentious to me. I could do it and I knew I was only aping depth without knowledge.

My mother still marks "A Rainbow of Tears" as one of the best things I have written, a fact as funny as it is slightly insulting with seven books published. How can I compete with that raw boy?

I tried poetry for years after, but without a connection to what I was writing, the effort only annoyed me. My cheeks would flush when given honest praise for a story or essay. When a teacher wrote on a report that she always looked forward to my assignments, as I had style, I couldn't stop smiling for a week. When someone even casually told me that they liked a poem of mine, I marked them as a fool trying to ingratiate themselves.

I joined the literary magazine in my high school, where I was exposed to much bad writing by nature of it being a high school lit mag. I left that club when I was handed five of an upperclassman's handwritten, A-A-B-B-C-C, unevenly footed poems to type out. I skimmed through them and saw someone even less able to connect with the point of poetry, but more deluded into thinking her being in love with her ex was worth publishing. I meant to go back to lit mag every week for over a month, but I thought about that folder of her terrible poems in my locker, at their accusation, and my stomach wouldn't let me. As a pompous ass then, when I told this story, I implied I was doing the literary world a favor by keeping doggerel from print. It was that I couldn't stand being a part of that system, of perpetuating the myth that poetry meant a damn. It was all make-believe without substance, all people trying to sound smart by rhyming "can" with "man," expecting no one was going to be the first to admit the Emperor of Poetry was naked.

The faculty advisor never asked for the poems back or wondered why I did not return to the club. I saw her daily and waited for that conversation, but she wasn't bothered. They received such a glut of student submissions that the girl's unedited contributions could be overlooked. I doubt even the girl noticed her poems were not in the next edition. No one read the lit mag except to check for their names in the index. We did not even read it to mock the work of our enemies.

I regret not typing out those poems, even if it didn't amount to anything more than my anxiety over them. I hated them as a reflection, but she didn't deserve them buried under my old social studies homework.

I did not care about poetry until college, when Professor Johnson said a poem we read was humorous. Everything clicked into place at once. Before that period, I read, analyzed, and did not care about poetry. After she said that, I understood.

I've known poets since and have sometimes liked something they had written. I've been to poetry slams and usually treated them with scarcely more reverence than the most self-serious movie on Mystery Science Theater 3000. There are a few poets I adore and have spent years trying to get my juvenile delinquents to try slam poetry, enticing them with Brenna Twohy and Neil Hilborn without success. I have watched Louder Than a Bomb with classes six times.

I rarely teach poetry with any success. My students have suffered through primary schooling that underscored that poetry was the privilege of obnoxious white people with the money to be useless. My students will rap, with few exceptions badly, but will roll their eyes when I tell them that rap is poetry put to a beat. I might as well sit backwards in a chair and stumble over urban slang for how likely the connection between rap and poetry seems to them.

In a way, it is karma. I refused any suggestion that poetry was a valid form of expression, now I spend a few weeks a year assuring disaffected teens that it is if they would only open my eyes. I tell them how much I detested poetry, which they believe since I tend to be honest with them. I explain how intricate and measured poetry can be, usually by a period of my dissecting Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art." And I fail to reach them as I was not reached. m sure there were a few middle-aged women writing poetry about love, sex, and cats, but only because there always is in these groups. When I try to envision others, they are all extras from central casting meant to suggest more people were in the room without giving them lines.

I don't know how long I lasted there. It was several months, but not a year. I felt over my head and inferior. I had no business around practiced adults, even if I suspected the practice was literary self-delusion. If I took something from the group beyond their faintly patronizing encouragement -- they treated every word out of me as though I were TS Eliot's Christ Child -- I can't recall it. Poetry seemed false and pretentious to me. I could do it and I knew I was only aping depth without knowledge.

My mother still marks "A Rainbow of Tears" as one of the best things I have written, a fact as funny as it is slightly insulting with seven books published. How can I compete with that raw boy?

I tried poetry for years after, but without a connection to what I was writing, the effort only annoyed me. My cheeks would flush when given honest praise for a story or essay. When a teacher wrote on a report that she always looked forward to my assignments, as I had style, I couldn't stop smiling for a week. When someone even casually told me that they liked a poem of mine, I marked them as a fool trying to ingratiate themselves.

I joined the literary magazine in my high school, where I was exposed to much bad writing by nature of it being a high school lit mag. I left that club when I was handed five of an upperclassman's handwritten, A-A-B-B-C-C, unevenly footed poems to type out. I skimmed through them and saw someone even less able to connect with the point of poetry, but more deluded into thinking her being in love with her ex was worth publishing. I meant to go back to lit mag every week for over a month, but I thought about that folder of her terrible poems in my locker, at their accusation, and my stomach wouldn't let me. As a pompous ass then, when I told this story, I implied I was doing the literary world a favor by keeping doggerel from print. It was that I couldn't stand being a part of that system, of perpetuating the myth that poetry meant a damn. It was all make-believe without substance, all people trying to sound smart by rhyming "can" with "man," expecting no one was going to be the first to admit the Emperor of Poetry was naked.

The faculty advisor never asked for the poems back or wondered why I did not return to the club. I saw her daily and waited for that conversation, but she wasn't bothered. They received such a glut of student submissions that the girl's unedited contributions could be overlooked. I doubt even the girl noticed her poems were not in the next edition. No one read the lit mag except to check for their names in the index. We did not even read it to mock the work of our enemies.

I regret not typing out those poems, even if it didn't amount to anything more than my anxiety over them. I hated them as a reflection, but she didn't deserve them buried under my old social studies homework.

I did not care about poetry until college, when Professor Johnson said a poem we read was humorous. Everything clicked into place at once. Before that period, I read, analyzed, and did not care about poetry. After she said that, I understood.

I've known poets since and have sometimes liked something they had written. I've been to poetry slams and usually treated them with scarcely more reverence than the most self-serious movie on Mystery Science Theater 3000. There are a few poets I adore and have spent years trying to get my juvenile delinquents to try slam poetry, enticing them with Brenna Twohy and Neil Hilborn without success. I have watched Louder Than a Bomb with classes six times.

I rarely teach poetry with any success. My students have suffered through primary schooling that underscored that poetry was the privilege of obnoxious white people with the money to be useless. My students will rap, with few exceptions badly, but will roll their eyes when I tell them that rap is poetry put to a beat. I might as well sit backwards in a chair and stumble over urban slang for how likely the connection between rap and poetry seems to them.

In a way, it is karma. I refused any suggestion that poetry was a valid form of expression, now I spend a few weeks a year assuring disaffected teens that it is if they would only open my eyes. I tell them how much I detested poetry, which they believe since I tend to be honest with them. I explain how intricate and measured poetry can be, usually by a period of my dissecting Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art." And I fail to reach them as I was not reached.

Soon in Xenology: Sanity. Writing. Summer.

last watched: Angel: the Series

reading: Fast Times at Ridgemont High

listening: Damien Rice