05.25.06

2:20 p.m. -Carl Sandburg

I'll die propped up in bed trying to do a poem about America.

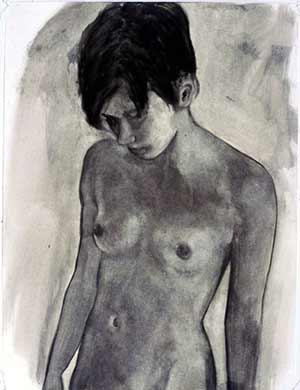

WARNING: this entry contains a breathtakingly beautiful sketch of a nude woman. If you aren't okay with that, you really are in the wrong place and I don't only mean this site.

Previously in Xenology: Emily's father was diagnosed with inoperable cancer.

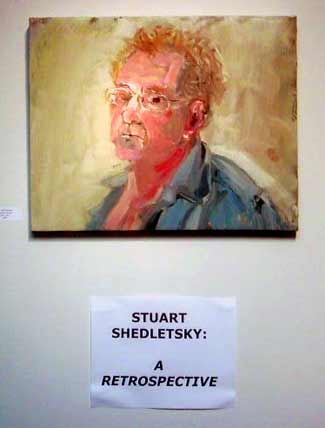

Brooklyn Artists Gym

I got off work early, which was fine since the library was desolately empty. Emily's sister had been working on an art retrospective for their father at a gallery in the city to coincide with his birthday. All of the publicity read that there was going to be a meet and greet with the artist, but he was deteriorating so rapidly that he no longer even passed through the threshold of his apartment to sit in the sun. His mind could not even retain the morning's sunrise and no one knew how many more he would get. A trip to Brooklyn would be immediately fatal and beyond ridiculous.

| |

| Rain doesn't actually melt witches. Thunder does. |

Half an hour late owing to traffic and construction, we arrived at Emily's mother's home in time to pick up her sister Lauren and her husband Chris. Her mother was a different story. She was visiting Stuart seven miles away. When we went to pick her up at Stuart's apartment, none of us entered. We only transferred to Judy's SUV. It was likely for the best given his condition, but it felt concertedly strange to be so close and yet so far. I guessed that he was in no position to receive visitors who were not immediate family or hospice workers.

On the way to the gallery, Emily marveled that I was so impressed by The Statue of Liberty. When I told her this was because I was seeing it for the first time, though at a distance of several miles, she pronounced herself remiss and promised she would take me there soon. It was her assumption that all school children are taken to Ellis Island before passing to middle school.

We met Emily's best friend Kelly at a French restaurant that wasn't worth the nationality. Emily and Kelly see one another infrequently, only a few times each year owing to the thousands of miles between them, though they still consider the other a best friend. I am not one to talk, as I give the title to people I have not seen in much longer who have less of an excuse. Emily says that, the moment they are in one another's company, it is as though they never left. Having lived together through college, the familiarity is that of sisters.

| |

| Brooklyn Artists Gym |

Emily's mother and actual sister left for the gallery before dessert for fear of missing any of the show, leaving Chris, Kelly, Emily, and me to find our own way to the gallery. But, as NYC streets are all alphanumerically organized, I couldn't imagine we would have a very hard time of it.

We saw the rain beating down in front of us, but we were still getting sunny sprinkles. There is ethereality to walking into the pouring rain from relative sunshine. It gently grates against instinct, which orders us away from downpours. Emily and Kelly tried to hide under Kelly's tiny umbrella and Chris, being a tall sort, caught the rain before it could get to us. I just walked, chilled but enjoying the sensation of knowing that this was the stuff of which memories are made. Years from now, I will remember that rain and there is holiness in that. Emily told me to stop being brave and stupid and get under the umbrella with her, but it barely contained both of their heads. If I joined them, one of them would get wet.

We ducked under an overhang at the next corner. The men inside the building, a combination Hispanic church and repair shop, smiled and waved at the shivering wet gringos on their doorstep. When the thunder crashed - which it did often - Emily jumped and clung to me. Lightning poses no problem for her, in it just a lethal dose of electricity shot at the ground fairly randomly. Thunder, however, is a very loud noise and is instinctively feared. Tell me about Intelligent Design again?

| |

| Retrospective. Used with permission. |

We walked through the lessening rain to the right street, which might have looked nicer thirty years and twenty graffiti artists ago but now looked ghetto enough to intimidate. Jutting out from a brick wall was a sign reading "BAG," the Brooklyn Artists Gym and our destination. We entered to a dirty, industrial staircase leading up into a dark, silent unknown. "It has been nice knowing you," I informed my party, "because I have seen this movie and it doesn't turn out well for us."

"My family pretty much depends of this place," Emily informed as we ascended the staircase, ready for a chainsaw wielding killer.

"What do you mean?" Kelly asked.

"My father sunk most of our savings into this place."

| |

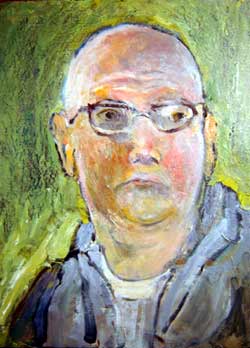

| Self-portrait, bald. Used with permission. |

"Dag," I replied helpfully, tracing a line in the dust of the banister.

The place was far from empty after we survived the staircase and a long hallway. Bits of paper bearing the legend "BAG" with an arrow were the breadcrumbs that pointed our path.

The lit room where the paintings were hung constituted only BAG's gallery. Poster and postcard propaganda explained that, for the low, low price of $200 a month, starving artists could practice their craft here. The conceit of Brooklyn Artists Gym is that it will be used as the equivalent of a gym, if one paid for 24 hour access and brought one's own TreadClimber; nothing is provided but space and bragging rights as far as I can tell.

| |

| Emily |

Immediately upon her entrance, Emily was lost in a deluge of well-wishers. Since Stuart would miss his show, Emily was given a camera to record the paintings and reactions thereto. At one point, a man rambled to Stuart via the camera about how much he looked forward to when Stuart got better. We wondered if he was ignorant of the truth or merely trying to say what he imagined to be most comforting.

I left her to her task and wandered, happening upon a girl named Abby Rabinowitz who looked pretty much exactly as a girl named Abby Rabinowitz ought. She was a childhood friend of Emily, though they lost touch and hadn't really spoken since high school - a fact that Emily had lamented to me on Monday. By Thursday, through a series of coincidences - none of which Emily initiated - they were having lunch together in the city, where they caught up on the past decade or so. They are both newly enrolled in city grad schools, Abby in Columbia and Emily in NYU, which will give them ample opportunity to catch up further.

| |

| Emily and Abby |

I started talking to Abby about Stuart's paintings, since she seemed like a good adoptive friend and it would give me something to do with my mouth that didn't involve nervously devouring the goat cheese appetizers to make up for the unfulfilling French meal from which I had come. I was basically parroting what Emily had told me about the paintings, though I added in that I tend to like art that looks like things. The abstract is only good to the extent that I can put things back together. Jackson Pollack would have hated me. In saying this, I was speaking specifically about the painting before us, one called "Narcissus at the Cave," which looked like nothing more than vivid lines and marshmallows. Abby took the stance that it did look like something it you applied the right eyes. I stepped back to argue that marshmallows were something and suddenly found the painting did look like something, flowers growing in front of a cave. None of the other of the paintings in his Narcissus series were blessed to resemble much of anything concrete, aside from a log balanced on a rock, and my assumption had simple been that this was likewise. I felt like a philistine ass, but to her credit Abby took it well.

| |

| Narcissus at the Cave. Used with permission. |

I had wandered the warehouse room in search of a specific series of sketches of a model named Shelton. They are amazingly passionate. They ooze. Yet all I could find were his paintings that, while superb, I had seen over a hundred visits to the Shedletsky household. I had only seen the Shelton pictures on the website for this show. Finally, someone led me to the hallway where they are being kept. The website did them no justice. I won't say that they are his best work, but they are the works with which I can most closely relate. They, if you will, look like things.

Finding Emily and another goat cheese aperitif, I said, "I keep looking around for Shelton."

"Don't bother," Emily told me, "she isn't here."

| |

| Shelton, 3. Used with permission. |

I craned my neck in hopes that a shorthaired woman would walk through the door anyway. "Oh."

"She isn't important anyway. She's just a model." Model was said will all of the inflection of "bowl of fruit" and for much the same reason. Having grown up with an artistic father, nude models had never been anything more than tools.

I did not fully embrace this stance of divorcing the subject from the piece and added needlessly, "I wanted to see if she has that beauty and passion or if it is something of your father."

"It is almost definitely my father."

"Still, if there were nude sketches of me being shown somewhere, especially ones of that caliber, I would make an appearance." One of the Shelton paintings, valued at more than I make in a month, became our property because Emily marked it with a red dot. In this way, we might have acquired a few other pieces, including a pig on the back of a horse.

I dithered about more as people chatted with and at Emily depending on the altitude of the video camera. The gallery was full of artistic lesbians, former students of Emily's father. I do not know for a fact that they all possessed alternate sexualities to match their nose rings, but the assumption seems a fair one and better helps you visualize the crowd. The young artists mostly chatted with one another next to the paintings. Had they seen these works before? Did they quite know what to make of them or was it enough to be there? I don't think any of them were there because they cared about the art, but solely about the artist and for one another. Though it, at times, had the air of a premature wake for me, I could not argue that this was a very happening place to have been. Events like art openings nourish my soul and I fully accept how utterly pretentious that makes me sound. As the lover-of-the-daughter-of-the-artist, I felt somehow more justified in being there.

As the event wound down, I approached a girl I had seen walking around, "Excuse me, but you look really familiar and I can't figure out how."

"I thought the same about you," the girl - Maia - replied. We did the brief exchange of possible paths the other might have crossed but came up wanting. "Maybe we know each other when we were elephants," she offered.

"Possible. I don't remember being an elephant."

| |

| As it Seems. Used with permission. |

Emily pulled me away, as it was well past time for us to make our exit, but was pulled away in kind by someone who knew her when she was a four-year-old making breakfast for schizophrenic. I grabbed one of the BAG postcards and scribbled "Thomm (former elephant)" and my e-mail address. Walking up to Maia, who was engaged in deep conversation with some of the artistic lesbians, I said, "I don't want to have to wait until I am an elephant again to talk to you."

She accepted it in a way I wish to believe was grateful. I can never tell how successful my gregariousness ever will be, though they few times it works are fabulous and life changing. If she never contacts me, so be it. My soul is satisfied to have made the effort. If she does not pursue, she was not intended to.

We walked the humid city streets back to the car as one loose amalgam of people, stretching half a block. I slowed down enough to hear Emily chiding her mother, "Peter isn't too young for you." The issue in my mind would be more that that Peter is Stuart's friend and business partner - he is the other founder of BAG - but I suppose the separation had been going on long enough. Still, I found the point an academic one.

"He is just a flirt," she responded.

"Yes, but he was flirting with you."

"He doesn't think I'm attractive, he's 45!"

I broke in, seeing a good opening for myself. "If I may be so bold, I think you are attractive and I'm 25. I was very pleased when I met you, since I knew that Emily would age very well."

"See, Thomm thinks you are attractive. You shouldn't write Peter off."

Emily and I dozed under a quilt in the back of the SUV on the way home, with visions of pigs riding horses dancing in our heads.

Soon in Xenology: Old friends and dreams.

last watched: Ice Age 2: The Meltdown

reading: Me Talk Pretty One Day

listening: Between the 1 and the 9