Fear and Trembling in the Hundred Acre Wood

As the more literarily aware of you may know, the estate of A.A. Milne has given permission for the creation of a new series of Winnie the Pooh books. And yes, for the rest of you, they were books long before Disney got their clutches on the rights.

Yet I am almost okay with the Disney-ification of the series. Sure, they were not as good and Disney created artifacts of these stories that simply should not be (seven-foot-tall Pooh costume, I am looking your way), but it was Pooh nonetheless. Hell, I could even stomach that damned miner gopher, as non-canonical and unnecessary as he is.

My issue can be summed up in one word: Girl. In order to appeal to "a new generation" of children, Christopher Robin is beating a dusty retreat to make way for some yet unnamed and computer animated tart. (Oh, they are all computer animated these days. You can't be hip unless it looks like some first year computer science major drew you on his Mac. I'm sure A.A. Milne would have given Pooh laser cannons if only the technology existed at the time, but I digress.) Disney apparently feels that a little girl was all that was missing from this fantastic universe.

Now before someone accuses me of stating that the Hundred Acre Wood is some sort of he-man women haters club, take a step back. Christopher Robin, neither the original nor the version sold by the cryogenic head of Walt, isn't exactly an Alpha male. He is just a little boy and, as such, he is androgynous. The creature who is replacing him is described in news articles as an "extreme tomboy," which is far more of a gender identification. None of Christopher Robin's problems were male specific, so the argument that castrating him and calling him Christina is going to attract the younger generation is ridiculous at the very least.

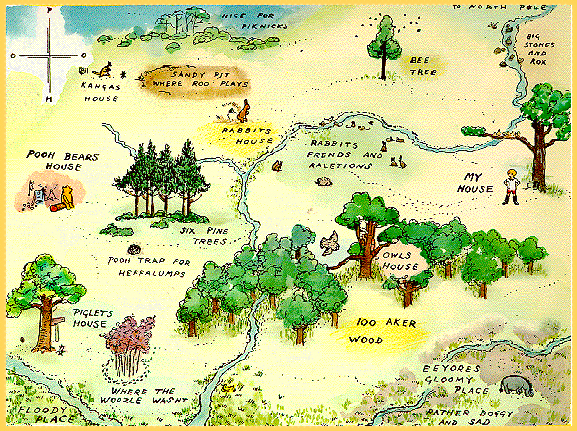

What you have to understand is that the Hundred Acre Wood belongs exclusively to Christopher Robin, no matter how much the A.A.'s son Chris grew to hate the stories... but we will get to that. (Also, please allow me the writer's indulgence of stating that I will distinguish between the storybook character and the person for whom he is named, as we have to understand them as separate beings. Therefore, Chris Milne shall be the man and Christopher Robin shall remain ever the boy.) Winnie the Pooh is Christopher Robin's stuffed bear, is he not? And, like many animate stuffed animals to follow -- most notably Calvin's tiger Hobbes -- is alive only in Christopher Robin's imagination. This is, in fact, the whole crux of my argument. The Hundred Acre Wood does not exist. This is self-evident to most of you, but let me clarify. Those of you familiar only with what Disney has done with the intellectual property may be unclear on the fact that Christopher goes from the real world into the imagined world of the Hundred Acre Wood in a way quite reminiscent of darling Alice into Wonderland. To reiterate, the Hundred Acre Wood is a projection of Christopher Robin's imagination and is therefore contingent on him to exist. If he does not perceive it, it simple is not.

Winnie the Pooh may be a tubby little cubby all stuffed with fluff while in the real world, but the psychic energy of the Woods casts him in a very different role. Pooh is Christopher Robin's spirit animal, the one being charged with leading Christopher through the maze of his own subconscious mind. All of the denizens of this realm have their symbolic role to play, corporeal examples of realities Christopher Robin cannot yet face. Tigger is a classic example of the id. He does what he wants when he wants it with very little forethought. He operates by the pleasure principle, but Rabbit, the superego, reins in even him. Yet how often do we see that Rabbit has caused more problems than he has solved, showing us clearly that the guilt placed on Christopher Robin by his caregivers is too strong. There will have to come a balance in the battle between the id and superego, but one side only aggravates and feeds into the other. The more Christopher Robin acts by the pleasure principle in the real world, the more guilt is impressed upon him by his mother and father, the more these internal archetypes fight for dominion and grow strong.

Do not think I have forgotten about the rest of the characters, though they are not as superficially significant as Pooh, Rabbit, and Tigger. However, their complexity betrays their importance. Piglet is a manifestation of Christopher Robin's fear; he is not safe even in his own mind. Kanga is obviously a Freudian representation of Christopher Robin's mother, with Roo playing the oppositional and necessary counter force. Roo is the child Christopher Robin was and still wishes subconsciously to be. You will note that Roo is almost exclusively portrayed in Kanga's pouch, which is a rather direct symbol for the vagina (no, really, what exactly did you think a kangaroo's pouch was?). Owl represents adults in general, at least in the symbolic language of Christopher Robin's mind. He is all bluster and knowledge, most of which is incorrect but which Owl will cling to with his typical pomposity. And Eeyore, with is dourness and pessimism, is Christopher Robin's externalization of his fears of the outside world. The books were first published in 1926, meaning that they were written in the aftermath of World War I; the world can not have seemed too bright to young Christopher Robin.

Christopher Robin must keep returning to the Woods to work through the primal traumas that caused it to form in the first place. At some point in his life, a great schism - some crisis beyond words - pushed his imaginary world from concordance with the real world. Only by living through these adventures that go on in this world he created, resolving the passion plays he unwittingly forces his archetypes to enact for his benefit, can he ever begin to grow up. He needs to get to that party where he can finally say goodbye to Pooh, can stop tossing sticks into the stream, can put away childhood things and finally become a man. Otherwise, he becomes yet another lost boy in a Neverland of his own making. He may think he is happy, but his psyche is far too fractured for him ever to be whole.

Does it therefore make the slightest bit of sense that a new person is trespassing on what is unquestionably the sacred ground of Christopher Robin's mind? Particularly given that I doubt this tomboy is an accredited therapist with appropriate licensure from the APA? We know that the real Chris Milne grew up to own a bookstore and publicly expressed hatred for his father's stories. He didn't fancy having the deepest regions of his unconscious mind scrutinized by glib internet columnists and read to small children as though this were nothing more than a bed time story. A.A. Milne ripped from his son the shroud of secrecy we all hold over our minds, offering them up to publishers near and far.

This tomboy should have her own imagined world in which to walk and work through a repressed sexual encounter or first awareness of her own mortality. The Hundred Acre Wood is personal and off-limits to persons not stuffed with cotton and psychoemotional detritus.

Xen is sending the text of these essays back in time to his prepubescent self using advanced technology and fairy dust. That you can manage to read them as well is only a glitch in the servers. Thomm Quackenbush is an author and teacher in the Hudson Valley. He has published four novels in his Night's Dream series (We Shadows, Danse Macabre, Artificial Gods, and Flies to Wanton Boys). He has sold jewelry in Victorian England, confused children as a mad scientist, filed away more books than anyone has ever read, and tried to inspire the learning disabled and gifted. He is capable of crossing one eye, raising one eyebrow, and once accidentally groped a ghost. When not writing, he can be found biking, hiking the Adirondacks, grazing on snacks at art openings, and keeping a straight face when listening to people tell him they are in touch with 164 species of interstellar beings.